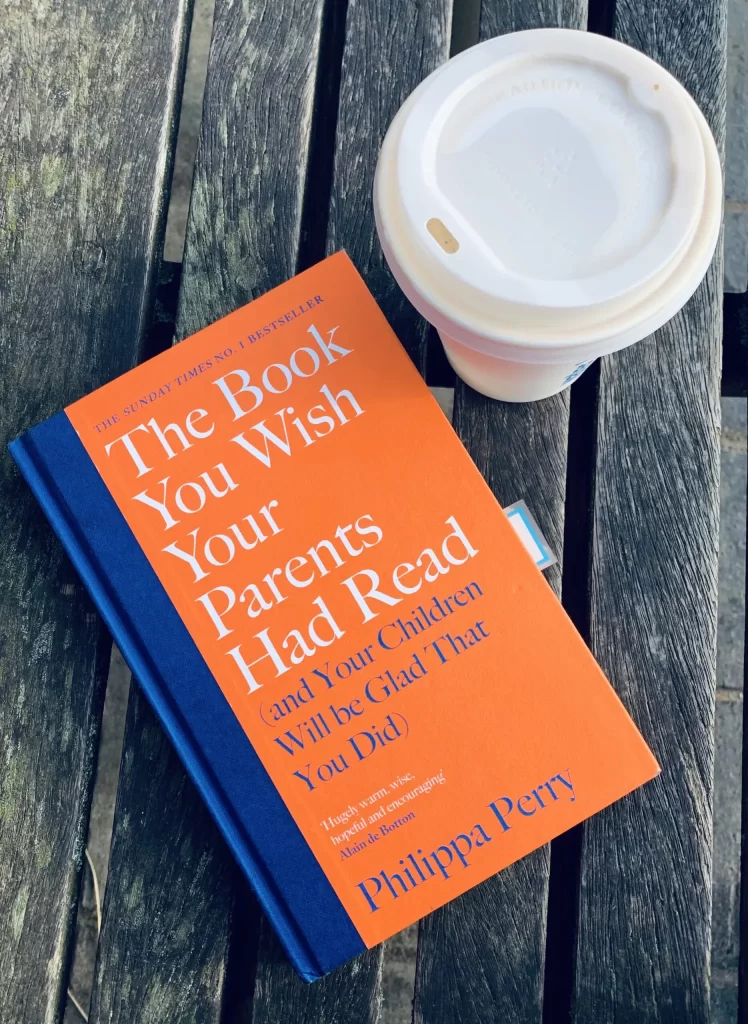

The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read. Book Summary

The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read. Book Summary

(and Your Children Will Be Glad That You Did)

Philippa Perry

Penguin Life (4 Feb. 2020)

About the author

After volunteering with the Samaritans, Philippa trained as a psychotherapist. She worked in the mental health field for several years before writing her graphic novel, Couch Fiction which lays bare the process of psychotherapy, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2010. Her second book, How to Stay Sane, was written for a series published by the School of Life and Pan Macmillan in 2012.

As well as continuing her psychotherapy work with an organisation called Talk for Health, Philippa has presented several documentaries including: The Truth about Children Who Lie; The Age of Emotion; and Humiliation for BBC Radio 4. For Channel 4 she has presented the documentaries: Being Bipolar; and The Great British Sex Survey. For BBC4 she has written and presented: Truth Lies and Love Bites, a history of Agony Aunts, and How To Be A Surrealist with Philippa Perry. Along with this, Philippa also created a cartoon agony aunt series for Guardian Video and has contributed to many other radio and television programs.

About the book:

“When you’re bogged down in the minutiae of nappies, childhood illness, tantrums (toddler and teenage), or when you’re doing a full day’s work and coming home to your real work, which includes scrapping banana out of cracks in the high chair, or another letter from the headteacher summoning you to the school, it can be hard to put being a parent in perspective. This book is about giving you that big picture, to help you pull back, to see what matters and what doesn’t, and what you can do to help your child be the person they can be.

The core of parenting is the relationship you have with your child. If people were plants, the relationship would be soil. The relationship supports, nurtures, allows growth – or inhibits it. Without a relationship they can lean on, a child’s sense of their security is compromised. You want the relationship to be a source of strength for your child – and, one day, for their children too. […]

I take the long-term view on parenting rather than a tips-and-tricks approach. I am interested in how we can relate to our children rather than how we can manipulate them. In this book I encourage you to look back at your own babyhood and childhood experiences so that you can pass on the good that was done to you by your own upbringing and hold back on the less helpful aspects of it. I’ll be looking at how we can make all our relationships better and good for our children to grow up among. […]

This book is for parents who not only love their children but want to like them too.”

The book you wish your parents had read (and your children will be glad that you did). What a great title for a parenting book! Although I’d been somewhat sceptical when I saw it, I was positively surprised when I started reading it.

Philippa Perry is a psychotherapist, a presenter, and a journalist (and an artist!) so the book is packed with anecdotes, both from her own family and clients, and it has plenty of research-based wisdom too!

In the book, she helps us understand how our own upbringing may affect our parenting, how to foster connection and nurture positive and long-lasting relationships with our children, how to handle our own and our children’s feelings, and also shows what different behaviours communicate to us.

I personally enjoyed the book and would recommend it to any parent who is trying to figure out what is really important in their parenting journey. If you are looking for a good read on gentle parenting, positive parenting, or conscious parenting – The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read is a great choice.

It is very engaging and packed with insights and practical exercises that would resonate with everyone. I’ll share just a few of my favourite insights in these notes, so grab the book for more!

Let’s jump in.

Key insights:

The past comes back to bite us (and our children)

“If, when you were growing up, you were, for the most part, respected as a unique and valuable individual, shown unconditional love, given enough positive attention and had rewarding relationships with your family members, you will have received a blueprint to create positive, functional relationships. In turn, this would have shown you that you could positively contribute to your family and to your community. If all this is true of you, then the exercise of examining your childhood is unlikely to be painful.

If you did not have a childhood like this – and that’s the case for a large proportion of us – looking back on it may bring emotional discomfort. I think t is necessary to become more self-aware around that discomfort so that we can become more mindful of ways to stop us passing on it. So much of what we have inherited sits just outside of our awareness. That makes it hard sometimes to know whether we are reacting in the here and now to our child’s behaviour or whether our responses are more rooted in our past.”

One of the key ideas in the book is that the way we were parented bounces back to us once we become a parent ourselves. So the first step to compassionate and gentle parenting is to understand which experiences from your own childhood may trigger the negative feelings and your reactions to your child’s certain behaviours. In short, to parent effectively, we need to unpack our own emotional baggage first.

That resonates a lot with Dr Shefali’s wisdom – in The Conscious Parent, she writes:

“Whether we unconsciously generate situations in which we feel the way we did when we were children, or we desperately struggle to avoid doing this, in some shape or form we inevitably experience the identical emotions we felt when we were young. This is because, unless we consciously integrate the unintegrated aspects of our childhood, they never leave us but repeatedly reincarnate themselves in our present, then show up all over again in our children.”

That’s why parenting is a great path to personal growth!

Feeling furious about your child’s messy play in the park? Retrieve the memory of yourself being a child when your parents discovered you playing in the mud and got cross. About to explode when your child throws a tantrum in the store because you refused to buy another Spiderman – look back at your childhood. We are conditioned by our parents’ reactions to our behaviours when we were children. And it becomes our autopilot.

You can rewire your autopilot baseline by making yourself aware of your triggers and deliberately choosing to react differently.

Question for you – which behaviour in your child triggers the most negative response in you? My two biggest triggers are whining and a mess!

It is not the rupture that is important, it is the repair that matters.

“In an ideal world, we would catch ourselves before we ever acted out on a feeling inappropriately. We would never shout at our child out threaten them or make them feel bad about themselves in any way. Of course, it’s unrealistic to think we would be able to do this every time. Look at Tay – she’s an experienced psychotherapist and she still acted on her fury because she thought it belonged to the present. But one thing she did do, and what we can all learn to do, to mend the hurt is called ‘rupture and repair’. Ruptures – those times when we misunderstand each other, where we make wrong assumptions, where we hurt someone – are inevitable in every important, intimate and familiar relationship. It is not the rupture that is important, it is the repair that matters.”

There are no perfect people. Nor perfect parents. We are all driven by the emotional brain, and no matter how hard we try to engage our logical brain to alter our behaviour in an emotional state, we will slip from time to time. And that’s ok. The main point here is to repair – apologize for your overreaction, schedule a special time with your child, play their favourite game – find the glue that will reconnect you.

In essence, that’s one of the best ways to foster a growth mindset in your child and yourself. It’s ok to make a mistake – learn from it and find a way to fix it!

Relationships, feelings and happiness

“The way we learn to relate to our parents and siblings is habit-forming, a blueprint for all our later relationships. If we get into a groove of having to be right, having to be the best, having to have material things, having to hide how we really feel, not having our thoughts and feelings accepted as they occur, these types of dynamics can put a brake on developing our aptitude for intimacy and our capacity for happiness. But validating our children’s feelings strengthens the bond between us and our child.”

Philippa dedicated the entire chapter to the importance of accepting and validating our child’s full range of feelings, from happiness to resentment. If we fully accept our children and teach them to express all their feelings appropriately – our relationship thrives. Whereas, if we shut them down when the negative feelings pop up or try to make them feel better instead of letting them metabolize these feelings, we may undermine their mental health in the future.

To do that, we, adults, should accept and validate our own feelings and needs in the first place. Remember, we set the tone!

That reminded me of Jesper Juul’s wisdom in his books (check out our notes on Your Competent Child and No!: the Art of Saying No! With Clear Conscience), where he repeatedly highlights that to parent effectively, we need to take our children AND ourselves seriously – that means we need first of all acknowledge that we all have a right to have the needs, desires, experiences, feelings and the right to express them, and secondly, see the children’s needs from their point of view.

In the book, Philippa shares communication strategies to express feelings and needs – and guess what? They all resonate a lot with the Nonviolent Communication approach (check out our notes – it’s truly life-changing).

And to wrap up:

“In our great need of wanting our children to be happy, sometimes we push them away when they are angry or sad. But for good mental health, children need to have their feelings accepted and to learn acceptable ways of expressing all their feelings – and the same is true for us adults. So it is important to accept our own feelings rather than denying them, and essential to accept our children with whatever they may be feeling too. By helping a child put their feeling into words (or pictures) we help them to process them as well as to find acceptable ways for them to communicate what they feel.”

Question for you – how do you react to your child’s negative feelings?

How we train our children to be annoying

“If babies and children don’t get what they need at the beginning of their lives, if they don’t feel seen, if they can’t be certain they will be responded to, they may get locked into the stage of trying to get attention. And that’s when you – and other people – might experience them as annoying.”

Attention-seeking behaviour is a real thing. If kids can’t get positive attention from parents at the early stage of their lives – they don’t feel seen, and they don’t feel secure – they’ll try to attract it in different ways. Because negative attention from a parent is better than no attention at all.

In a nutshell, the more positive attention you give to your child, the less annoying behaviour you’ll see.

So now – what is positive attention? Philippa explains that children need ordinary turn-taking, the to and fro of spoken or unspoken dialogue. That includes:

- responding to your baby’s cues

- showing reciprocity

- empathetic listening

- engaged observation

Same as Stephen Covey in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Families and Laura Markham in Calm Parents, Happy Kids, Philippa writes that one of the most effective strategies to foster connection with our child is Love Bombing – that’s technically the one-on-one Special Time with your child when they take the lead on what to do, what to eat and how to dress, while you just spoil them and shower them in love ☺

Put your phone away

“If you’re physically close to your child but are missing their cues because, say, you are on your phone or computer, it will trouble them. […]

We know that alcoholics and drug addicts do not make the best parents because their priority is always the substance they’re addicted to, so their children are denied a lot of attention they need. I’d say phone addicts are not so far behind. I do not recommend checking emails on your phone in front of a young child for long periods of time. Not only will you be depriving them of contact, you will be creating an empty space inside them. And not to be dramatic, but this is the sort of empty space that may make addicts of people later in life, when they try to fill it with addictive substances or compulsive activities to stop a feeling of being disconnected – feeling empty – haunting them.”

That’s a compelling and brutally honest message. I’m getting super annoyed when a person with whom I’m trying to connect stares at the phone all the time. I bet you do too. Guess how a child feels when the most important adult in his life prefers a phone to him?

If you want to witness the immediate effects of screens on the parent-child connection, check out this amazing TED Talk by Molly Wright:

To get some ideas on how to break your phone addiction, check out our notes on Bored and Brilliant by Manoush Zomorodi and Irresistible by Adam Alter.

Behaviour is communication

“Behaviour is purely communication. People – and especially children – act out inappropriate, inconvenient ways because they haven’t found alternative, more effective, more convenient ways of expressing their feelings and needs. Some children’s behaviour is inconvenient to others, but it is not ‘bad’.

Your job is to decipher your child’s behaviour. Rather than dividing our children up into ‘good’ bits and ‘bad’ bits, there are questions you need to ask. What is their behaviour trying to say? Can you help them communicate in a more convenient way? What are they telling you with their bodies, with their noises and with whatever words they may choose? And, a really hard question to ask yourself: how is their behaviour co-created with yours?”

Decoding our child’s behaviours is probably one of the most important parenting skills. Once you figure out the key reasons for a behaviour, you can teach the child to express their needs and feelings in a more convenient way. And last but not least, model the desired behaviour yourself!

I first had this aha moment while reading Mona Delahooke’s great book Beyond Behaviours. She offers us to picture any behaviour as a tip of an iceberg, and I think it is super helpful for understanding this big idea:

“…think of behaviours as the tip of an iceberg—that part of an individual that we readily see or know. The tip reveals answers to “what” questions about a person. Just as we can see only the tip of an iceberg, while most of it remains hidden underwater, we can observe childhood behaviours with the understanding that the many factors that contribute to them are hidden from view.”

P.S.: “Dig deeper – behaviours have meaning” is one of my 12 Commandments of Parenting 😉 It now pops up as a tattoo on my brain when dealing with my kids’ challenging behaviour!

The qualities we need to behave well

“Your job is to model good behaviour, to behave towards your child and towards other people with the same empathetic attitude and hope your child will adopt this behaviour too. As well as that, there are four skills we all need to develop in order to become socialized, to behave conveniently.

These are:

1. Being able to tolerate frustration

2. Flexibility

3. Problem-solving skills

4. The ability to see and feel things from other people’s point of view.”

That’s a brilliant summary of the most crucial executive skills every child needs to master to thrive in life.

So instead of punishing kids for their “inconvenient behaviour”, we need to direct our effort at teaching them the skills they need to behave well. That’s what positive discipline is all about.

And that totally resonates with Jordan Peterson’s Rule 5: Do not let your children do anything that makes you dislike them. To socialize your kids well and teach them how to behave appropriately, you need to help them develop these four essential skills.

Everybody lies

“All children lie; all adults lie too. It’s great when we don’t, because it gives us a better chance to have a proper dialogue and intimacy. But we all do it and we shouldn’t treat our children like the greatest sinners when they do too.”

That’s a big one. When you catch your child in a lie, your job is not to react but to understand the reason behind that lie. Were they scared that you’ll freak out and be furious? Did they want to get out of trouble? Fantasy lies? Lies to please a grown-up?

And here is one more thing to remember:

“The more judgemental you are, the more punitive you are, the more you will stop your child confiding in you.”

Action steps for you:

- Invest as much positive energy in your child as possible – connect with your child daily (e.g. through play, empathetic listening, engaged observation, at the dinner table) and let them feel seen and safe.

- Reflect on your triggers and look back with compassion: “Ask yourself what behaviour in your child triggers the strongest negative response in you. What happened to you as a child when you demonstrated the same behaviour?”

- Approach your child’s inconvenient behaviour as a detective: ask yourself, “What is their behaviour trying to say? Can you help them communicate in a more convenient way? What are they telling you with their bodies, with their noises and with whatever words they may chose? And, a really hard question to ask yourself: how is their behaviour co-created with yours?”

Quotes from the book: